This page is under development and eventually will give you all the (background) information you need to plan your trek on the Pamir Trail. There is advice on terrain, weather, equipment but also how to minimise your impact, how to organise your transport and food along the trail as well as how to do a visa run. The latter is needed when you plan a thru hike.

If you read this on your phone, keep it horizontal for a better reading experience.

Accommodation

Along the Pamir Trail you can find various types of accommodation. In the more popular mountain areas, such as the Fann Mountains and the Bartang Valley you can find many home stays. In the bigger towns you may find a guesthouse or hotel. But for each section on the Pamir Trail you need to carry a tent, as certain stages are too remote or there is no formal accommodation in the particular village/town where a stage ends. Below we explain a bit more how home stays work. We also provide a comprehensive list of accommodation (both home stays and guesthouses/hotels) for each section of the trail.

Home stays

Home stays in Tajikistan are formalised accommodations in people’s homes. Often these home stays are located in rural villages with the aim to attract tourists and have them experience the real Tajikistan. It is a genuine, authentic experience and we recommend everybody visiting Tajikistan to stay at least one night in a home stay. The owners have received hospitality training, but this is something that’s engrained in Tajik (Central Asian) culture anyways. Often you sleep in a common room, possibly with other guests. In some cases home stays have private rooms but don’t count on it. The stay includes a local dinner and breakfast and is served on a table cloth (dastarkhon). You sit cross-legged around the dastarkhon. Toilets are shared and almost always outside the house in a far corner of the premisses. Make sure you have a head lamp or torch handy as there is likely no light to guide you in the night. Toilets are generally very rustic and is often not more than a hole in the floor. In all fairness it’s not a very pleasant experience. Expect to pay between $20-$25 per night including the meals.

How to you ask if there is a place to stay at in Tajik: Ask “Hast mehmonkhona?” while point at the village. This just means “is there a guesthouse?” while also referring to hotels, homestays, and single guest rooms within a house. The “kh” should be pronounced roughly the same as “ch” in German (or as a plain “h” if you can’t make that sound).

Sometimes locals take you in without being an official home stay. This happens mostly when it’s late in the day and they feel responsible for your well-being. It’s ok to accept this and is a wonderful way to have a peek inside Tajik rural life. Try to leave a decent amount of money when you leave. The host will refuse but try anyways. For more information on cultural conduct, we strongly recommend reading this chapter, see here.

Hotels and guesthouses

In bigger villages and towns you may find more formal types of accommodations like guesthouses and hotels. Check the price upfront before you agree to stay. We are in the process of mapping all accommodation along the Pamir Trail. In some places there might be a place to stay but it isn’t listed on the (for tourists) conventional platforms such as Google Maps, Booking.com and AirBnb. You can ask around and if there is something people will guide you to the place.

We made a provisionary list of places to stay on the Pamir Trail. Click here to access the Google Sheet with the list. It is incomplete and we are working on adding more details such as accurate phone numbers and coordinates. Eventually we hope to list the home stays on a booking platform suitable for this type of accommodation.

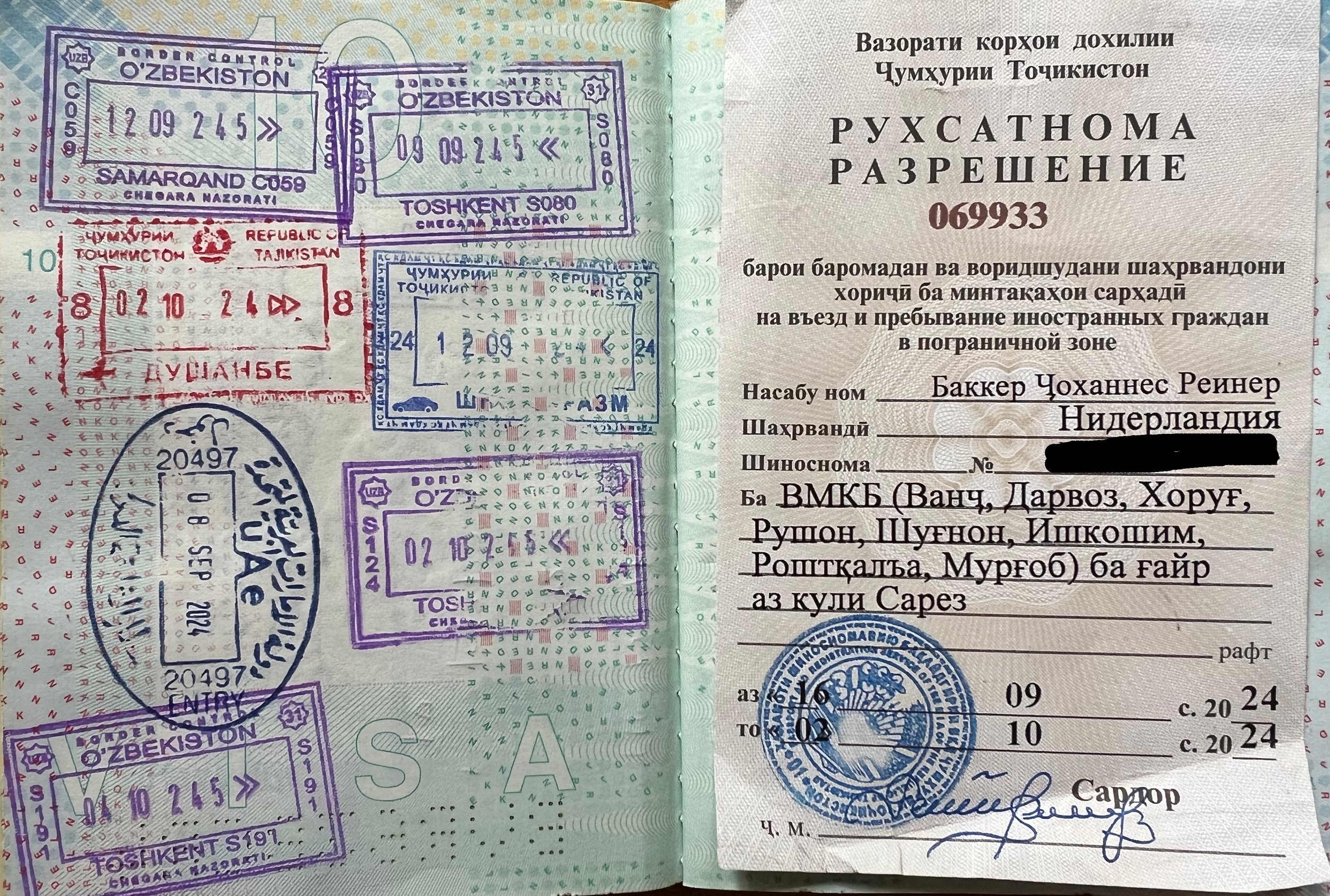

Visas and permits

The visa regime in Tajikistan has come along way, making it easier for travellers to visit the country. Below is a summary of the various options to enter Tajikistan.

Visa free, visa on arrival and e-visa

Citizens from more than 80 countries including all EU member states as well as the US and Australia are eligible for the visa free entry. It allows you to stay for 30 days. Note that it does not include a GBAO permit, that allows you to enter the Pamirs (and hike section 6-9). Also you need to register with OVIR (migration authorities) of you stay longer than 10 working days in Tajikistan. More detailed and up to date information about visa free entry and visa on arrival check the well-informed Caravanistan website.

Some would choose to apply for an e-visa. This visa allows you to stay 60 days, it has the option to include a GBAO permit and you don’t need to register with OVIR, saving you time. If you stay for longer than 30 days this would be your best option. Applications can be made on the official website evisa.tj. Other websites are agents and probably add a hefty “processing” fee. Note that the application process is fickle. Sometimes it’s done quickly, sometimes nothing has moved after a month. There are ways to speed up the process, of course with a price tag. Get in touch as we may be able to help out. For thru hikers 60 days is likely to be too short as the Pamir Trail has 80 stages. In the next paragraph we’ll share a strategy to do a visa run to Uzbekistan.

Visa run for stays >60 days

If you are planning to stay more than 60 days you will have to go for a visa run. Thru hikers are advised to head back to Dushanbe after section 5, travelling from Jirgatol (officially Vahdat these days). There are many mashrutkas (mini-vans) heading to the capital. From there you travel to border of Uzbekistan. Again, check this page on Caravanistan how to organise this. Now the tricky bit. You technically cannot obtain a second e-visa until you exited Tajikistan on your first e-visa. You may start the application process before you do the visa run, but it won’t be approved until you’re out. You probably need a contact to speed up the process, as you don’t want to waste waiting for the approval. We may be able to help out, please get in touch if this is the case. Note that US citizens under the age of 55 need an e-visa for Uzbekistan!

GBAO Permit

You are obliged to get the GBAO permit to enter the Pamirs / Badakhshan. It costs around $10 per person and you can get it with your e-visa or in Dushanbe. Sometimes it’s easier to get this via a local tour operator. We can help with this.

National Park Fees and Restricted Areas

Along the Pamir Trail you will go through three national parks: Yaghnob National Park, Sangvor National Park and the Tajikistan National Park (often referred to as Tajik National Park). In 2024, the entry fee to any national park in Tajikistan was raised from $2.5 to $10 per day. As for now, the collection of the entry fee for Yaghnob has not been enforced yet. However, you are required to pay the fee for Tajik National Park. You will cross the national park on section 6 (stages 52-54), section 7 (stages 60-61) and section 8 (stages 66-70). A ranger will come to you, there is no need to find an office, because there is none. Do ask for an ID. If no one approaches you, well, then you get a free ride.

The only restricted area you will pass on the Pamir Trail is Lake Sarez (section 8, stages 66-67). You need a permit for this and permits are only issued for guided treks with a minimum of two people. We are currently developing an alternative route via the Bardara Pass to avoid this obstacle. If you move as part of an organised trek, then the boat will take you from the monitoring station at the Usoy Dam (which also serves as a guesthouse) to the meteorological station at Irkht. The Sarez permit is $25/day and the boat $50/person. Double check in Barchidev with Nurmamad (who runs the homestay) if there is enough fuel at the monitoring station. If not make sure fuel is transported there. He is in charge of the Sarez permits and coordinates the boats. We strongly recommend to make the Sarez arrangements with Pamir Eco Tourism, who are from Barchidev. They communicate swiftly and have all the local connections to make the process smooth.

Photo: Jan Bakker

Logistics: food and transport

Logistics in Tajikistan is a complex and potentially expensive business. There is no efficient system for deliveries, the public transport system is underdeveloped in the rural regions and fuel is not cheap, unlike in neighbouring countries like Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Re-stocking supplies in the villages is somewhat possible, but the choice in the village shops is generally very limited. If you do multiple stages, you will have to organise some food drops, organised from Dushanbe or Khorugh (Khorog), depending on the trail section. We will share some tips, tricks and contacts to organise food drops and drop off and pick up to and from the trail.

Ways to organise food drops

There are 3 ways to organise your food drops.

First you could use a shared taxi and travel along the main routes to the taxi hubs or directly to start or end of a section. For this you need to speak Russian and / or Tajik, as you may never see your food package again. It’s the cheapest but also the most risky way to distribute your re-supply. Later in this chapter we outline all the potential pick up places and transport hubs.

Second you can use a company to do this for you. This is more expensive, but at least you know you have food throughout the trek! The Pamir Trail works with trusted partners to fulfil this service for fair prices. In high season you may be able to share logistics with other trekkers. We coordinate this through our Pamir Trail 2025 WhatsApp group.

Finally, you could rent a car and do the drops yourself. We advice to rent a high clearance 4X4 as some access roads can be rough. Get in touch with us to inquire about a rental vehicle.

Food drops and transport section 1-6

Logistics on the northern sections 1-6 of the Pamir Trail are generally a little easier to organise than in the GBAO region, apart from the two Langar hubs. We work with our partner Archa Foundation to organise the food drops and transport to the trailhead and trail end. You can reach them via email or WhatsApp. You can also drop us a line and we can hook you up. Potential drop off points are:

Section 1: Zimtud (after stage 3), Alauddin Lake (after stage 6), Saratoq (Sarytag) (after stage 11)

Section 2: Hushyori (on stage 18 on the M34)

Section 3: Margheb (after stage 24)

Section 4: Langar - Zarafshon Valley (after stage 31, remote and expensive to organise)

Section 5: Navobod (after stage 37), Hoit (after stage 41)

Section 6: Vahdat (Jirgatol) (after stage 43), Langar - Sangvor District (after stage 47, remote and expensive to organise)

Note that we haven’t established partnerships on some of these drop off points but we hope to have this sorted before the trekking season starts. For your personal drop offs and pick ups before and after the trek you can use these hubs as well. Prices fluctuate sometimes as these are linked to the market price for fuel in Tajikistan.

Food drops and transport section 7 -9

For the GBAO region (Pamirs) we work with TransOxiana Outfitters, based in Khorugh (Khorog). You can reach them through email and WhatsApp. These are the food drop hubs for the Pamir region.

Section 7: Qalai Khumb (after stage 51A if you do the low route on section 6A), Vanj (after stage 55B if you do the high route on section 6B), Motravn (after stage 58), Rushon (after stage 61, could also serve as a cheaper re-stocking point for section 8)

Section 8: Nisur (after stage 64)

Section 9: Varshez (on stage 71), Rubot (after stage 74)

All the food drop points that are mentioned have either accommodation or a shop with basic supplies or both. Basic supplies means they could sell super noodles, pasta, rice, some vegetables and fruit, candy etc. Keep in mind that things do run out of stock. We highly recommend to stay at a homestay on the PT. Staying at a home stay saves you weight, gets you delicious freshly prepared local food and it’s a great way to support the local communities. Here’s the list of homestays along the Pamir Trail, that can help you organising your food plan as well.

Note that between Qalai Khumb and Vanj there is no reliable form of transport (and the road is often closed 6 hours per day for road construction that will not be completed for many years). Unless you pre-organised a car, you will have to either hitchhike or find a local car to take you there. The stretch between Rushon and Nisur is on the Bartang (dirt) road. If you want to skip this part on foot you can arrange a private taxi or if you’re lucky a shared taxi.

Photo: Martina Merisi

Low Impact Trekking

The mountains of Tajikistan are hardly visited by foreign tourists and therefore the effect of tourism on the mountain environment is still minimal. This doesn’t mean the mountains are devoid of humans. In late spring shepherds move from their winter homes in the lower regions to the summer settlements closer to the high grazing grounds. The arrival of single use plastic and the continuous deforestation puts a strain on Tajikistan’s mountains. You can make a difference by minimising your own impact and inspiring others, including locals, to do the same. This chapter aims to give you ideas how you can minimise your environmental impact on the Pamir Trail, both while trekking in the wilderness and in the villages.

Rubbish / litter

The most visible environmental issue in this part of the world is rubbish. In rural Tajikistan there is no formal way to dispose of rubbish. Often the waste is deposited into a large pit or worse, it is tipped off a steep slope (river bank or ravine) outside of the village. As a visitor you can make a difference by making sure you’re not creating rubbish in the first place. Refuse single-use plastic bags and bring dry bags or reusable ziplock bags instead. You could repack your supplies before you head for the mountains. Carry all rubbish out and take it to the nearest town where waste disposal is better organised. Batteries should be taken home with you as there are no facilities in Tajikistan to recycle these. And if you have the choice, choose paper or cardboard packaging over plastic. The latter essentially doesn’t bio-degrade, it just breaks down in small particles. Avoid buying bottled water but bring a reusable water bottle and/or hydration bladder. You can filter or purify the water, also when you’re in an inhabited environment.

Human waste

Human waste is another potential environmental and health threat. If human faeces enter the water supply that people rely on for drinking and preparing food (for example a river or a lake) it could threaten the health of an entire community. As a trekker you can do two things. The first option is to bury the faeces. In an arid environment like the Tajik mountains you should dig a shallow hole of around 10cm deep and at least 50m away from a body of water. Make sure you fill up the hole again. Toilet paper should be carried out or burnt (only if the direct environment doesn’t pose a risk of wildfire). Urine is less harmful but do make sure you pee away from streams and lakes.

Camp fires

Trees are generally scarce in Tajikistan. The species that is most commonly found in the Tajik mountains is juniper. It has a very slow growth and plays a crucial role in preventing soil erosion and as a consequence mudflows and landslides. Harvesting wood from juniper trees is strictly forbidden by custom and law. Despite this nearly 70% of the forests have been cut in the last half century due to the energy crisis after the fall of the Soviet Union. Deforestation still continues. A great source of fuel is yak and cow dung, which is only found at higher altitudes where yaks roam. If you’re camping at an established (shepherd’s) camp spot then use the existing fire place.

Use of soap and detergents

Washing yourself, your clothes or the dishes should be done with a biodegradable soap. Biodegradable might suggest that you can safely use it directly in a body of water, but this is not the case. Do the wash (including yourself) at least 50m from any water surface to avoid harming the aquatic life. A foldable jerry can is a useful piece of equipment for this purpose.

Erosion

If there is an obvious clear trail, then stick to the trail. On some sections the trail is not heavily used. It might fade in which case you try to follow the logical route and try to avoid causing erosion and stepping on flowers and plants.

Local outfitters

The trekking industry in Tajikistan is still in its infancy and most outfitters haven’t been in the business for very long and they might not have an environmental policy. If you plan to use a local operator to tackle (parts of) the Pamir Trail it’s worth asking some critical questions. How do they deal with the rubbish? What fuel is used for cooking and do they support wildlife conservation initiatives? Do they organise hunting trips as well and if yes, do their hunting practices comply with the conservation policies? As a client you are ultimately responsible for the impact your party has on the environment. Your local crew (guide, cook, animal handlers) are often uneducated and have limited environmental awareness. It’s up to you to make sure they leave the camp clean, even if they leave after you. Make them prove they take all rubbish out. A good practice is to designate a place for the latrine. Urge the support staff to use this latrine as well.

Photo: Martina Merisi

Culture, Languages and Cultural Awareness

The territory of Tajikistan has been part of the Silk Road trade route for millennia and has therefore been exposed to foreign visitors since ancient history. The famed hospitality in Central Asia is deeply rooted in the culture and Tajik people are honoured to receive guests in their home, whether they are friends or complete strangers. By immersing yourself in the local traditions, you will win the respect from your host. It will give you an insight in the local way of life and it makes interaction much easier. Tajik rural life is far simpler than modern-day occidental lifestyle and spending some time in a Tajik mountain village will raise existential questions about what really matters in life. Traditions are homogenous across the country with some slight differences from region to region.

Religion

The predominant religion in Tajikistan is Islam. In the Pamirs, most people are Ismaili, a branch of Shi’a Islam that follows the Aga Khan as its spiritual leader. Elsewhere in Tajikistan people are Sunni. After the collapse of ideological Soviet Union, religion has slowly (re)gained influence in daily life. Ramadan is widely respected among Sunni Muslims and when visiting Tajikistan during Ramadan keep in mind that it could affect your travel plans. Everything slows down in daytime and the celebration at the end of Ramadan (Eid al Fitr) is a national holiday. Especially during this period pay close attention to your driver as they may not have their full attention on the road. Some regions are more religious than others. In general, the deeper you go into the mountains, the stricter people practice their religion. The upper Zarafshon Valley and the Gharm and Sangvor (Tavildara) areas are known to be religiously very traditional. The people of the Pamirs are Ismaili Muslims, but the religion is interwoven with Sufism and Zoroastrianism. They pray one to three times a day and have always done their prayers at home rather than a designated communal place.

Language

Tajikistan hosts a kaleidoscope of languages and differentiates itself from the Turkic dominated languages elsewhere in Central Asia. Tajik is a Persian language, similar to Dari in Afghanistan and Farsi in Iran. Some argue Tajik and Dari are both local dialects of Farsi. Tajik is spoken nationwide although each region has their own dialect. It evolves constantly as scholars add new words from Farsi and replace the Russian words that have been incorporated during Soviet times. The country was created by merging ethnically different regions together. The remote corners of Tajikistan are often inhabited by non-Tajik speakers. In the very north of the country, the Shugd region, people speak Uzbek while the eastern Rasht Valley and the eastern Pamirs are home to a Kyrgyz minority, speaking Kyrgyz.

In the rest of the Pamirs most people speak Shughni, an older language than Tajik but also within the broader Iranian language family. It’s an oral language and an alphabet in Roman and Cyrillic script was only created 70 years ago. Although some books are being printed in Shughni, the language is not taught in schools and is not recognised as an official language. Most valleys have their own local dialect such as Bartangi in the Bartang Valley and Wakhi in the Wakhan Valley. Russian is still widely spoken by the generation that went to school in Soviet times and by Tajiks who have spent time in Russia as migrant workers. Gradually English is taking over as the foreign language for the new generation. In the guidebook Trekking in Tajikistan you can find a comprehensive language guide specifically for trekking related topics.

Hospitality

Tajiks welcome their guests very warmly. It is a pleasure and an honour for them to welcome visitors at their homes or to have them around for celebrations and weddings. Travelers are compulsory offered an invitation into the house for a cup of tea, often accompanied with yoghurt, bread and a variety of sweets. You can test the real motivation of your host by refusing three times. If the invitation is offered a fourth time it’s genuine and your encounter will likely be a great cultural experience should you accept the invitation. The hospitality is not limited to short breaks. The Tajik feel obliged to help travelers with food and a shelter for the night. Keep in mind that an invitation may mean that the host cancels other plans for the day to accommodate the unannounced guest. It also involves a lot of work and extra expenses. It is more respectful not to rely on local hospitality when travelling in rural Tajikistan and to plan food and shelter accordingly, while keeping some flexibility in your schedule for a beautiful, unexpected encounter. It is appropriate to leave some money (comparable to the price of a homestay) when staying overnight at a house. If the host doesn’t accept it at first, insist and add some good arguments for example, the money is for the children to buy books and school supplies. This usually breaks the resistance. If not, you can leave the money underneath the tablecloth. A Tajik proverb says that hospitality is granted for three days during which the guest can rest entirely and then must leave or work, often added with the joke that the guest returns the fourth day to rest for another three days.

Food and table rituals

Bread or non is the cornerstone of the Tajik diet. It’s a large, flat bread that is baked in a strongly preheated tandoor oven. It accompanies all meals. To the Tajik, throwing away bread is sacrilege so respect this attitude! Non is carefully laid facing up and your host will share it by breaking it into several pieces. The festive dish is plov (fried meat with rice, carrots and onions) and it is served during important events such as rural weddings, guests visiting and funerals. Kurutob is a traditional dish made of oil, flat bread and dried cheese softened in hot water. In rural villages people still rely heavily on what is produced at home (potatoes, eggs, meat and yoghurt in summertime) and usually have a limited variety of dishes to offer. For vegetarians it’s even a bigger challenge to eat a varied vegetarian diet in rural Tajikistan.

Sitting cross legged on thick carpets (kurpachas) around a tablecloth spread on the floor (dastarkhon) is the most common way to eat. If this is difficult for you, tell your host and they will find a way to accommodate you. Make sure you never step over the dastarkhon and avoid pointing the soles of your feet directly towards somebody else. Eating can be done with your hands or with cutlery. Wash your hands in both cases and only eat with your right hand if no cutlery is presented to you. Tajiks, like in many other cultures, prefer to eat with hands as they say it is tastier this way. Give it a try and eat your plov with the right hand! Some dishes are presented on a common plate with everyone sharing the food. The usual way to share a common plate is to take a bite with your spoon, lay the spoon with the back on the rim of the plate and take another bite once you have swallowed the previous spoonful. When sharing a meal it is always appreciated you share some of your personal food that you carry around. It breaks the monotony of the local shepherd’s diet that mainly consists of tea, rice and bread. Chocolate and fruits are highly valued.

In some remote and religious areas, female travelers may be asked to eat with the local women and not to share the meals with men. Food is generally prepared by women and they often don’t join for dinner with guests. It is ok to offer help with picking the vegetables prior to the meal, clearing the dastarkhon or cleaning the dishes. It could be a way to connect with the otherwise invisible ladies. When the meal is finished people commonly close dinner time by saying omen, putting the hands together and move them from the top to the bottom of the face. This is to thank for the food.

Tajik homes and staying the night

When you enter a home in Tajikistan, always take off your shoes or boots at the entrance unless the host suggests otherwise. Sometimes there are slippers for guest use, but it is a good idea to bring your own indoor footwear. In rural areas houses often have two rooms: the main (living) room and the guestroom. If guests spend the night, the family sleeps in a separate room. Female guests may be offered to sleep in the company of the grandmother or a young lady, for company or in case something is needed. It is inappropriate if a man offers his company and should be politely rejected. Sleeping is done on kurpachas that are stacked on the floor and is surprisingly comfortable. The toilet is often a small building outside with a hole on the ground. In some cases it is shared with other villagers. Bring your own (head)torch and toilet paper.

Dress code

The dress code varies from Dushanbe, where life is more liberal, to rural areas, where women still wear modern variations of the traditional dress and trousers combination, known as the kurta. In general, the rule “don’t show too much skin” is well applied in Tajikistan. The culture is modest and women don’t show their legs and shoulders. Tight clothes, shorts and tank tops can feel stared upon in rural Tajikistan. For a woman, it is proper to wear trousers and even better long skirts. Being lightly dressed can be interpreted as being sexually available. From a practical viewpoint, it’s more comfortable to wear light trousers that will prevent sunburn and scratches from the thorny low vegetation, and stop the yughan plant from burning your skin (read below for more info on yughan). Men may feel uncomfortable wearing shorts in traditional areas as the local men don’t. Some female travelers may feel more at ease wearing a head scarf loosely worn behind the head, but this is absolutely not necessary. Being clean will earn you respect from the locals, expect not to be treated so well when you’re dirty and dusty. It’s not easy to stay clean while trekking so it’s worth packing a clean shirt and light trousers in case you pass a village or city.

Greeting and addressing people

Greeting between men is done by a right handshake and placing the left hand on the heart. Close friends and relatives greet by hugging and kissing the cheek three times, starting on the right side. In the Pamirs, men kiss the hand. Women greet men by placing a hand on the heart and nodding and sometimes by shaking hands if the woman is ok with this. Women shake hands when meeting for the first time and kiss on the cheek when familiar with each other. As a foreign man avoid shaking a local woman’s hand unless she offers a handshake. Kissing between partners is not a public affair and frowned upon. Friends may hold hands.

Tajik culture makes it easy to address people you don’t necessarily know by name. An elderly man with a respectful white beard can be addressed as Bobo (grandfather), an elderly woman as Bibi (grandmother), a man older than you as Aka and an older lady as Apa (which means older sister). Young boys are referred to as Bacha and Dukhtar is a young girl.

Women travelers

Travelling by yourself as a female in Tajikistan is safe. People are respectful and will help you as much as they can. It’s still best to behave modestly and follow simple advice like in any other country: avoid drinking with a group of men, avoid sleeping in the same room with men you don’t know and be a little sceptic with people in authoritative positions like police and military. Community sense and social control are very strong and misbehavior won’t go unnoticed. Let people know where you are going to and you’ll be looked after by the community.

Gifts

In general, you should avoid giving small gifts or treats to children. They are well taken care of by their families. If you are interested in engaging in and supporting local communities it is more meaningful to enquire about community projects that are in need of support and you could make a donation to these.

Photo: Martina Merisi

Trekking Season and Climate

The trekking season in the Tajik mountains is short. The high mountain passes are blocked by deep snow most of the year, river levels are high during spring time and early summer and temperatures are well below freezing level at higher altitudes. In general, the best time to go trekking is from June to early October. Outside this period, it is still possible to go trekking but you have to be prepared for very cold conditions at higher elevations.

Precipitation

In the Fann Mountains, the Hisor Range and the Zarafshon Range (sections 1-4), depending on the snowfall in winter, mountain passes may still be covered until late June. The Pamirs, which receive less precipitation, may have accessible passes earlier but high areas like the high areas between Sarez Lake and the village of Bachor (section 8) should not be attempted before the end of May. In summer time expect frequent but short-lived rain showers in the Fann Mountains and the odd snow shower on the passes. The Rasht Valley (sections 5 and 6) can also be rainy at times. In the western Pamirs weather patterns between the north and the south are quite different. The southern valleys of Wakhan and Shakhdara (section 9) are much drier as they are in the rain shadow of the Hindu Kush. The northern valleys of Bartang, Yazghulom and Vanj (section 7) receive much more precipitation, influenced by the humid weather patterns of the Pamir Alai in the north. The eastern Pamirs are dry and barely receive any precipitation at all during the summer months. However, snowfall could occur even in summer in all mountain areas above 4000m.

Temperatures

Summer temperatures in the lower valleys of the Zarafshon Range can easily exceed 30°C. In the Pamirs daytime temperatures are often pleasant, even above an altitude of 4000m. Bear in mind that the wind can make the temperature feel much colder. At night the temperatures plummet in the single digits and even below freezing, though the average freezing level in July and August is normally above 5000m. Winter is brutally cold and temperatures of -30°C are not uncommon. Bulunkul is officially the coldest inhabited place in Central Asia where the mercury once dropped to a whopping -63°C.

Wind

Winds follow patterns that are common for mountain valleys: up valley during the day and down valley at night. Winds are particularly strong in the eastern Pamirs, the Shakhdara Valley and the Wakhan Valley.

Climate change in Tajikistan

Tajikistan has a fast-growing population. This, combined with the deforestation, has accelerated the already ongoing effect of global climate change. It is causing severe irregularities in climate patterns: spring and autumn are longer and warmer, winters are shorter and spring sees heavier but shorter periods of precipitation. The intensity of showers and abrupt rises in air temperature has triggered numerous devastating debris flows and landslides in recent years.

Weather forecast

A good source of weather information for the Tajik mountains is Meteo Blue (meteoblue.com) or Mountain Forecast (mountain-forecast.com).

Photo: David Burwick

Safety and Security

General Security

To some the “Stans” evoke associations with extremism, drug trafficking and corruption. Although one shouldn’t treat the “Stans” as a single entity with a generic security problem, the issues mentioned do exist, also in Tajikistan. However, there is more nuance to it and most travellers/trekkers won’t have issues while visiting the country.

The civil war (1992-1997) that started after the break-up of the Soviet Union has left a terrible legacy that has cost many lives even after the war ended: landmines. Border areas and strategic valleys and mountain passes have been mined. De-mining agencies have cleared large areas since and continue to do so but Tajikistan is far from mine-free. Especially the border area with Afghanistan and the inner regional borders in the northern Pamirs (section 6 Sangvor/Tavildara and Rasht) still have areas with marked and unmarked minefields. The trekking route across the Gardani Kaftar Pass (stages 45-47) has a small but manageable landmine issue. Known minefields are marked with a red sign or the zone is fringed with white rocks. Risk areas include the Pamir Highway, specifically the part north of Qalai Khumb and the region Tavildara. The latter was mined during the civil war and the clearing has not been finished to date. Some of the valleys around Jirgatol are still contaminated with mines as well. In any case, in these areas don’t stray off the road and keep yourself informed by the locals.

Some mountain valleys, notably Tajikistan’s regions of Rasht and Badakhshan (GBAO) are strongholds for anti-government movements. Occasionally violent clashes erupt with government forces, the last one dating from 2021 in the towns of Khorugh (Khorog) and Rushon. The GBAO region may be suddenly closed to foreigners for a prolonged time without prior notice. Check with the Pamir Trail team before you head out to GBAO for the latest updates.

Currently there is no evidence in recent years that members of extremist groups like Taliban, Al Qaida and ISIS cross into Tajikistan from Afghanistan. Since the retreat of international forces from Afghanistan and the installment of a Taliban government, the Tajik border patrol has intensified since. Having said this, tourists are welcomed in Afghanistan and you can even cross into the country with a visa on arrival at the landborder of Shir Khan Bandar.

Corruption is still widespread in Tajikistan and it’s not uncommon that travellers experience it first-hand. Examples include handing over a passport to a police officer and having to buy it back or an airport official fishing out dollars from your wallet in a back room as a “penalty” for taking out too many US dollars out of the country. Never hand over your passport but give a colour copy of the passport and visa pages instead. If the police officer insists seeing your real passport ask him to take you to the station to see the chief of police.

Safety while trekking

The biggest safety issue for trekking in Tajikistan and the Afghan Wakhan Corridor is the remoteness of the trekking routes. A minor problem like a twisted ankle can turn into an epic as any form of help is potentially days away. There is no rescue service with the same resources as in the Alps or Nepal. In Tajikistan the mountain search and rescue team will be dispatched by the Committee of Emergency Situations and Civil Defence (they will arrive in camouflage uniforms, but shouldn’t be mistaken for the military).

It’s always a good idea to bring a mobile phone with a local SIM card. Tcell and Megafon has the best coverage in the Tajik mountains, but don’t assume you have phone reception. An increasing number of trekkers bring satellite based communication devices like Garmin InReach, Zoleo, or a sat phone. In 2024 a successful rescue operation was triggered when an InReach device sent out a distress signal in a very remote part of the Pamirs. The search and rescue team of the Committee of Emergency Situations and Civil Defence helped stranded trekkers crossing an uncrossable river (Yazghulom) with a dinghy. It took two days to reach the trekkers. Although the story ended well it does illustrate that help is far away. Take a Search and Rescue insurance as these operations are extremely expensive.

The terrain in the Tajik mountains is ever changing due to the forces of nature. Each year avalanches, flash floods, debris flows and rock fall change the landscape and wipe away the fragile mountain infrastructure built by the mountain’s inhabitants. Due to climate change debris flows become more frequent, more violent and is causing significant damage. Especially in early trekking season (until the end of July) the volume of rivers can change rapidly and turn into raging torrents. When choosing a camp spot make sure it’s at a safe distance from the river or stream, if possible. Pay special attention to your environment when a few very hot days have occurred as it may cause (meltwater) debris flows. Another sensible thing to do is to think through a plan B. Pathways and bridges could be washed away and bad weather could stop you from crossing a high-altitude pass, forcing you to rethink your trekking journey. You may have to reroute your trek, supplies permitting. In the worst case you may be forced to turn back.

A number of mountain passes involve walking on a glacier. Early in the season some of glaciers are still covered with snow. Some glaciers are crevassed and you can only cross if the glacier is snow-free. This particularly applies to the glaciers on the Dugdon Pass (section 1), Starghi Pass (section 6) and Odudi Pass (section 7). The use of crampons is recommended or even necessary in some cases. In the equipment chapter we specify on which sections you should carry crampons and axe.

Shepherd dogs

Every shepherd will have a number of dogs to herd and protect their sheep and goat herds against predators, in Tajikistan mostly wolves and bears. These dogs are bred to fight predators, hence they are very strong, fearless and aggressive. Most of the time the dogs will let you know that you’re approaching their territory by barking loudly. Assess whether there are people around to keep them under control. If this is not the case try to find an alternative route or wait until the flock has moved on.

Photo: David Burwick

Staying Healthy

There is a number of things you can do at home to reduce the chances of getting ill during your visit to Tajikistan. It starts with paying a visit to your GP or a specialised travel clinic. Ultimately, they will give you the definite advice on vaccinations and prophylaxis. Currently the immunisations that you should have are the cocktail of DTP (diphtheria, tetanus and polio) and hepatitis A. Other recommended vaccinations are against typhoid and rabies. Tajikistan is regarded as a high-risk country for rabies and as a trekker in remote mountain regions a vaccine buys you time when you’ve been bitten by a suspect animal. Malaria is present in the southwest of the country although if you head straight for the mountains there is no need to take anti-malarial prophylaxis.

It’s a good idea to do a dental check-up before you go. At higher altitudes underlying dental problems may be exposed by the change in air pressure. Nothing worse than an aching tooth and not a dentist around for hundreds of kilometres. Bring a nail clipper and keep both toe nails and finger nails short. And make sure you (re)break in your boots properly at home to avoid blisters during the trek. You don’t have to be a professional athlete to do the treks but needless to say keeping a good level of fitness makes the experience more enjoyable and avoids unnecessary injuries. Before you go you need to think through what medical supplies to bring in your first aid kit. In the remote Tajik mountains you need to be self-reliant. Below is a suggested but not exhaustive list of first aid items you should pack. Quantities depend on the length of the walk.

Suggested medical items

Anti-septic wipes

Non-woven gauze swabs in different sizes

Wound dressing

Zinc oxide tape

Woven bandages

Triangular bandage

Steri-strips

Plasters

Blister plasters (like Compeed)

Tweezers / scissors

Safety pins

Ibuprofen / Paracetamol / Aspirin

Sachets of Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS)

Anti-histamine

Water purifying tablets

Insect repellent / sting relief

Anti- diarrhoea treatment: activated charcoal and Smecta

You could ask your GP/doctor to subscribe antibiotics like Ciprofloxacin (Cipro). Explain you are visiting a remote mountain region with no medical services. Ciprofloxacin (Cipro) can be purchased without a doctor’s prescription/script at almost every pharmacy/chemist in Tajikistan. Ask for “tsipro” or show them the name in Russian: Ципрофлоксацин. The stronger antibiotic Azythromycin is also available from local pharmacies. Russian name: азитромицин. Cipro is about $2 per pack, and Azythromicin is about $5 in local phramacy/chemists.

Water and Food

Most health problems in Tajikistan are related to water and food. Water, whether it’s from a tab or from a stream should not be assumed drinkable throughout the country and should always be filtered, boiled or treated with purifying tablets. Livestock roam the mountains up to very high altitudes and could contaminate a seemingly clean stream of water with bacterial infections like Giardia and cryptosporidium. It’s worth buying a water filter to take out bacteria. The water will taste better than using the other options and it reduces your environmental footprint by not buying plastic bottles. If you are trekking with a local crew make sure they boil the water with an additional minute of boiling time at higher altitudes. To avoid cryptosporidium, a filter is the best option, as chemical treatments that are effective against crypto can take 4+ hours depending on water temperature and clarity.

Traveller’s diarrhoea is the most common illness among visitors to Tajikistan and is often a result of poor hygiene. Wash your hands with hand sanitiser or normal soap after every toilet visit and before every meal. Urge your trekking crew to do the same. If you do get Traveller’s diarrhoea make sure you drink plenty of fluids, preferably mixed with ORS and try to eat light food like rice, mixed vegetables, soup and bananas. Take activated charcoal and Smecta (clay) for treatment. In case the diarrhoea persists for more than 4 days, it is better to head back to Dushanbe for a proper check-up. It is advised to do a stool analysis at the Iranian hospital or Shifo. Giardia and amoebic dysentery are not uncommon and require an anti-biotic treatment. If the latter is left untreated it could have severe consequences including liver and brain diseases.

Sun and heat

As a trekker you are exposed to various environmental factors with the sun as the dominant force. At lower elevations it gets very hot with temperatures rising to over 40°C. Heatstroke and dehydration are the biggest health threats. Try to avoid walking at the hottest time of the day (between 11am and 3pm) and wear a hat to protect your head. Drink a minimum of 4-5 litres a day and more as you gain altitude. The strength of the sun in this part of the world is brutal and increases significantly as you head to higher grounds. Protect your skin and lips with sun cream and UV lip balm (minimum factor 30) and wear long trousers and long sleeve shirts.

Yughan plant

While trekking in an area with high vegetation pay close attention to the plant “Yughan” (“yugan“ in Russian) from the family of Umbelliferous. It is quite noticeable thanks to its height and the bright yellow flowers. Its sap, when touching the skin, become photosensitive and can cause up to second degree burn marks. If this happens wash the exposed part of the skin with soap as soon as possible and cover it to avoid sun exposure. Antihistamines may help to soothe the affected skin.

You can avoid yughan by wearing long pants and not touching low green plants with your bare hands. Photos of yughan plus comprehensive information on avoiding yughan at this link. By late summer and early fall the plant is dried out and no longer green, becoming harmless. But it may persist in shady areas and moist soil.

Altitude sickness

With an average elevation of 3187m Tajikistan is the third highest country in the world after Nepal and Bhutan. All of the multi-day treks in this book will reach altitudes of over 3500m with the highest point exceeding the 5000m mark. Some of the trailheads are well above 3000m and prior acclimatisation is strongly advised. The amount of oxygen in the air decreases as you ascend to higher elevations; the air gets “thinner”. Most people won’t have any problems with the drop in oxygen levels up to 2500m. Above this altitude the human body starts to struggle. The heart needs to work harder to pump the same amount of oxygen to the lungs. Even when resting the heart rate is much higher than at sea level. Mild symptoms may appear such as loss of appetite, light headache, difficulty sleeping, dizziness and fatigue. Some body parts could swell up like your hands, feet and face. This is normal and if you stay around the same altitude for a couple of days these symptoms should fade away, which is the process of acclimatisation. The general rule is to roam high and sleep low. In theory you shouldn’t sleep more than 300m higher than the previous night, but this is not always feasible. If you ascend too quickly mild symptoms may become more severe and could develop into severe Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) that manifests itself in two forms: HAPE (High Altitude Pulmonary Edema) and HACE (High Altitude Cerebral Edema). Both conditions are instantly life threatening and need to be addressed at once. HAPE is a condition when the lungs are filled with excess fluids. A person basically drowns in his own fluids. Symptoms of HAPE include breathlessness while resting, having a rasping / crackling sound while breathing, a fast heart rate and coughing up frothy, pink coloured sputum. HACE is a condition when the brain fills with fluids, causing it to swell. Symptoms include lassitude, irritable and confused behaviour, a constant splitting headache, difficulty with mental and physical coordination and if untreated the victim slips into a state of coma and certain death as a final result.

Acclimatisation is key to prevent AMS. Especially when you go trekking in the Pamirs you should study the altitude profile carefully and if needed build up your acclimatisation by staying at intermediate altitudes before commencing the trek. If time is limited you could consider acclimatising at home in a relatively new invention called the hypoxic tent. At night you sleep in a low-oxygen chamber, adapting your body artificially to higher altitudes. Medicine like acetazolamide (sold under the brand name Diamox) and dexamethasone are sometimes used to prevent altitude sickness. If the symptoms of AMS are severe the ONLY treatment is to descend to lower elevations. This should be at least 300m but the further a victim descends the bigger the chance of a speedy recovery. If Diamox or a similar drug is available use it this buys you time to get to a more oxygen-rich environment. In the PECTA office in Khorugh (Khorog) and possibly Murghob (Murghab) you can find hyperbaric chambers also known as Gamow bags to find further treat AMS. Remember that both HAPE and HACE are indiscriminate to gender and fitness levels.

Make sure you have a comprehensive travel insurance that covers trekking as an activity and includes Search and Rescue and medical evacuation.

Photo: Martina Merisi

Trekking Equipment

What to bring on a trekking expedition requires thorough planning, especially when you’re off to do an adventurous trek like the Pamir Trail. There are still no specialised outdoor equipment stores in Tajikistan so everything has to be brought with you. The choice of food and equipment for a trekking expedition is very personal. It depends on the style of trekking and the length and character of a trek. Do you want to bring “luxury” food or are basic food supplies enough to keep you going? In long-distance hiking weight is a crucial factor. You can spend a fortune on high performance ultra-lightweight equipment and freeze-dried food. The art is to buy kit with the best price-weight-performance ratio. To some extend this applies to food as well. Freeze-dried meals are expensive but they decrease the weight of your pack dramatically and give you the calories you need. With a little effort you can create your own lightweight meals for a fraction of the price of a freeze-dried meal. More on food in the chapter Transport and Resupply.

Trekking style is the decisive factor what you will put in your pack or duffel. You could roughly divide trekking styles in supported and unsupported. By supported we mean a fully supported trek as they are generally organised in Tajikistan. This includes guide, pack animals, cook and food and some camping equipment. Unsupported is exactly what it says on the tin. You deal with the organisation of the trek yourself from A to Z.

Packing, sleeping and eating

Those who venture into the mountains unsupported are likely to choose a lightweight approach. Everything needs to be carried in a backpack. A pack can be as small as 40L up to 80L for those who focus less on the weight. To organise your stuff inside your pack you can use dry bags in different sizes. This way you can quickly access the item you need and it stays dry should it rain or snow. Bring a 3-season tent with a footprint. Camping grounds sometimes have a rough or soggy surface. A sleeping mat keeps you insulated from the ground surface. A foam mat is harder to sleep on but doesn’t puncture and is great to use during a break. Inflatable mattresses have a higher insulation value and are more comfortable but (small) punctures are sometimes difficult to repair. Pack a down sleeping bag. Down packs small and is lightweight. Use a liner to keep the bag clean and to get some extra insulation. On sections 1-5 you can get away with a comfort rating of around -5°C. In the Pamirs, camp spots are generally higher and hence it is colder. Make sure your down bag has a comfort temperature of at least -10°C. Some of this equipment is available for rent with our partner Archa Foundation in Dushanbe and at the PECTA office in Khorog office. Choosing the right stove for Tajikistan is personal. Screw top gas canisters are available in Dushanbe (Green House Hostel, City Hostel and the “20 Calibre“ hunting and camping store at its new location). You would have to organise resupply drops across the trail as you won’t be able to find these anywhere else. Multi-fuel stoves from brands like MSR and Primus are reliable, And it’s easier to find fuel along the way. However, you do need to filter the petrol (with for example a stocking) as it can be dirty. Bring an additional maintenance kit as well. Carburetor cleaner is available in all car maintenance shops throughout Central Asia and great for cleaning your fuel stove. Fuel bottles can be filled at a large busy petrol station where petrol is cleaner. Other items to bring for cooking are lightweight cutlery, pots, wind and waterproof matches and a couple of lighters, a mug and an Aero Press or coffee filters if you can’t function without coffee. For hydration make sure the capacity is at least two litres. This could be a combination of a water bottle, hydration bladder and a thermos, depending on your personal preference. You might want to bring a water filter to ensure clean drinking water.

Clothes and footwear

The choice of footwear also varies among long-distance trekkers. On the Pamir Trail large parts are doable with trail runners. The first thru hikers did the entire PT on this type of footwear. They used shoe gaiters to avoid sand and stones getting in their shoes and micro-spikes for glacial terrain and steep solid mud, scree or gravel walls.

High walking boots are the most common choice and especially in scree / blocky terrain this is preferable. Take your time fitting boots and try them at home so you can still return them. Once you made the choice break them in properly. Leather and fabric ones both work. Fabric boots are sometimes lined with a waterproof and breathable membrane (such as Gore-Tex). For the northern section 1-5 you might want light and highly breathable footwear without this lining as it is hot. For some mountain passes the use of strap-on crampons or micro-spikes are recommended. The terrain can be very rocky and you might have to cross scree and boulder fields for a prolonged time. The bottom line is that within the given parametres, your boots need to be comfortable. Don’t forget to pack a pair of spare laces! Sandals with straps or neoprene water shoes are useful for river crossings and camping.

You will probably experience big temperature differences during some trekking days. It’s good to think about the layers of clothing you’ll be wearing before setting out. Mornings can be cold and you may be wearing three layers of clothing. Once the sun gains strength you probably want to take off one or two layers to avoid overheating. The base layer could be merino wool thermal underwear and liner socks, depending how cold it is. The second layer is a pair of light or mid-weight socks (preferably merino wool), trekking trousers and a fleece jumper or soft shell jacket. The third layer just for the upper body is probably the most vital piece of clothing in your pack, a breathable waterproof jacket. It keeps you protected from the elements and truly is a potential life saver. For breaks you might want to pack an insulated jacket as well, both down and synthetic will do the job. This is also good when you’re camping at high altitude. Bring a brimmed cap to protect your head from the sun and a wooly hat to keep the head warm. A Buff is a very useful item for sun protection and it can cover your nose and mouth when it’s dusty. Bring a pair of fleece gloves and a pair of warm waterproof gloves. Make sure you take enough spares for items you wear directly on the skin like thermal underwear, t-shirts and socks.

Electronic equipment

In the digital age it’s very likely that trekkers will have a number of electronic items on their pack list. Although electronics are not crucial, they can improve safety, logistics and recording the trek. A mobile phone is almost a necessity. These days everybody uses a smart phone for navigation with apps like Komoot, Outdoor Active, OsmAnd, Mapy.cz. These apps are useful and quite accurate. But absolutely don’t count on it as a safety back up! The same applies for the camera on smart phones. Officially it’s not allowed to bring in drones. Having said that, lots of travelers have managed to get one in the country. A Kindle enables you to bring as many books as you like without the weight. Satellite communication has become more mainstream and bringing a sat phone (Thuraya has the best coverage in Tajikistan) or satellite messenger such as a Garmin InReach or a Zoleo whilst on trek to communicate with your loved ones or if things go wrong with the emergency services.

The mobile phone coverage in Tajikistan is ever increasing and it is handy if you need a car at the trail end or something has happened and you need help. However, since October 2023 the ability to buy a SIM card or e-SIM and a local plan has become more restrictive. The most difficult scenario encountered by some has been the need to register their phone (specifically the IMEI number) at the Dushanbe airport - a paid service. Following this you must go to the OVIR office in Dushanbe and secure police registration. Once you have these two documents you can then go into the office of a local phone company to buy a mobile phone plan. If you somehow manage to find someone to sell you a plan without registration, know that your phone will be blocked on the network within 10-30 days. Whether or not the online registration system works is unknown.

Another complication is that there are multiple mobile phone companies, and there is often just one of them servicing small villages in the mountains. There is no one single company or plan that will work across all areas. Locals who need to travel and work across different regions and in the smallest villages often have bought a SIM card from every mobile company in Tajikistan. One way to avoid the need for all this complicated registration and mobile plan purchases is to have an offline map download of the entire country, and comprehensive plans made well ahead of time. And if you have a satellite SMS plan with Garmin, Zoleo or another company, you can send text messages to phone numbers and email addresses (to arrange for pick-up and resupply, for example).

To charge all these devices bring a fully charged power bank. For power banks and charging, bring a 30 watt charger (with European plugs, not with a travel adaptor). A standard low watt charger is too slow for a guesthouse with one wall plug/outlet to share among 4 guests, or at a guesthouse that doesn’t have 24 hour electricity. And bring a fast charging power bank that can input 30 watts. An example of a 30 watt charger is the “Anker Nano 30W charger.” Power banks that input 30 watts of fast charging are uncommon. Good options here include the “Anker 537 Power Bank” (24,000mAh) and the smaller “Anker Nano Power Bank” (10,000mAh). Most high quality USB-C cables are 30 watts or higher. Just make sure to bring a long cable, as electric outlets in Tajik houses can be unreasonably high on the wall.

Other essential items

Other essential items include a head torch with spare batteries or a rechargeable battery, a multi tool, sewing kit, cable ties and duct tape for repairs, a pair of walking poles for river crossings and walking downhill, sun cream (at least factor 30) and UV protecting lip balm, a pair of sunglasses, hand sanitiser, biodegradable soap, nail clipper, toothbrush and toothpaste, a small towel, first aid kit (see the chapter Staying Healthy what the contents should be), a topographic map of the trekking route (downloadable per stage under the The Trail page) and last but not least a compass. For women a mooncup is very useful as sanitary pads are only available in larger cities. Make sure you rinse the mooncup with purified water.

Photo: Jan Bakker

Navigation

In general, navigation on the Pamir Trail is not that hard. Although there are no trail markers, the landscape is big and distinct and the visibility is mostly excellent. Navigation in let’s say the Scottish Highlands is infinitely harder. But it is important to note that the terrain in the Tajik mountains is very dynamic and the route may be blocked / impassable by landslides, flooding, avalanches etc. You must be able to make a sound judgement on how to navigate around those unexpected barriers. Sometimes this means you have to go back and travel around the impassable area.

We’ll share our experience on different ways to navigate the Pamir Trail.

Paper topo maps

Unlike most mountain ranges in Europe and North America, there are no accurate, up to date physical topographic maps for the Tajik mountains. Decent topo maps have been produced in the Soviet era, but these are not available in print (anymore) and were produced in the early nineties. You can still get those maps digitalised and they can serve as a reference. You can find an app here. There’s a fine map of the Fann Mountains produced by EWP available here.

Digital topo maps

So how should you navigate the Pamir Trail? The easiest tool to find your way is using offline Open Street Map-based map applications on your smart phone. There is quite a lot of choice, but on the trail we prefer using either the OsmAnd Map app (the most comprehensive) or the Mapy.cz app (amazing mapping layers and very readable), both based on Open Street Map. For both OSM and Mapy.cz a person should get the paid versions to get all the needed features (like map updates). Other map apps are very out of date or omit important features and objects on the map.

We do use Outdoor Active for the overview maps on our website and this app could work as well. You can download the GPX file for each section and apply them to your map application of choice. You should understand how to use these maps before you go and make sure you can use the maps off-line. On most of the Pamir Trail there is no phone reception. Also make sure you have a fully charged power bank handy, as navigating on your phone slurps battery life. When it’s obvious where to go, turn off the navigation to save battery.

Creating your own paper topo maps

For those who love maps and are keen to produce their own, there is a fantastic map making tool on Ink Atlas. You upload one or more GPX files, select the map area and determine which scale you want to create the map. It produces the map and you can download them in high resolution. You may want to laminate the map(s) for use on the trail.

GPS devices

Using a hand-held GPS device is also a legit way to navigate the Pamir Trail. Just transfer the GPX files from our site and off you go!